Montreal-based GHGSat’s sky high vision of emissions reduction boosted by alliance of Alberta oil sands producers

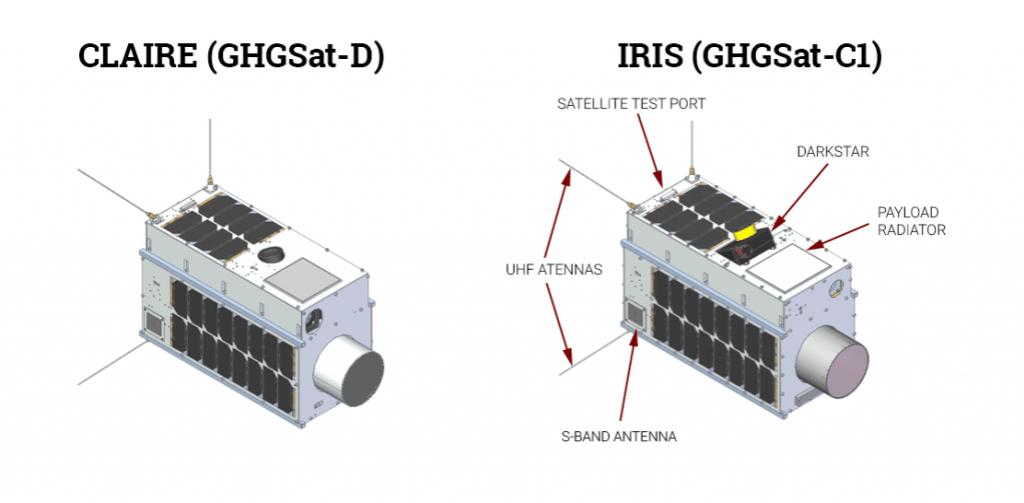

“The detection threshold on Iris is ten times lower than on Claire, which will give us more precise readings,” says Germain, president and CEO of GHGSat, which launched its first orbital methane-scoping probe in 2016, thanks to a collaboration between the company, Canada’s Oil Sands Innovation Alliance (COSIA) and Suncor Energy Inc.

The skybound sisters, who will be joined near the end of the year by Hugo (each of the satellites is named after real-life children of GHGSat team members), are specifically designed to monitor methane emissions, a greenhouse gas that packs 25 times more global warming potential than carbon dioxide and accounts for about one-fifth of the warming the planet has encountered.

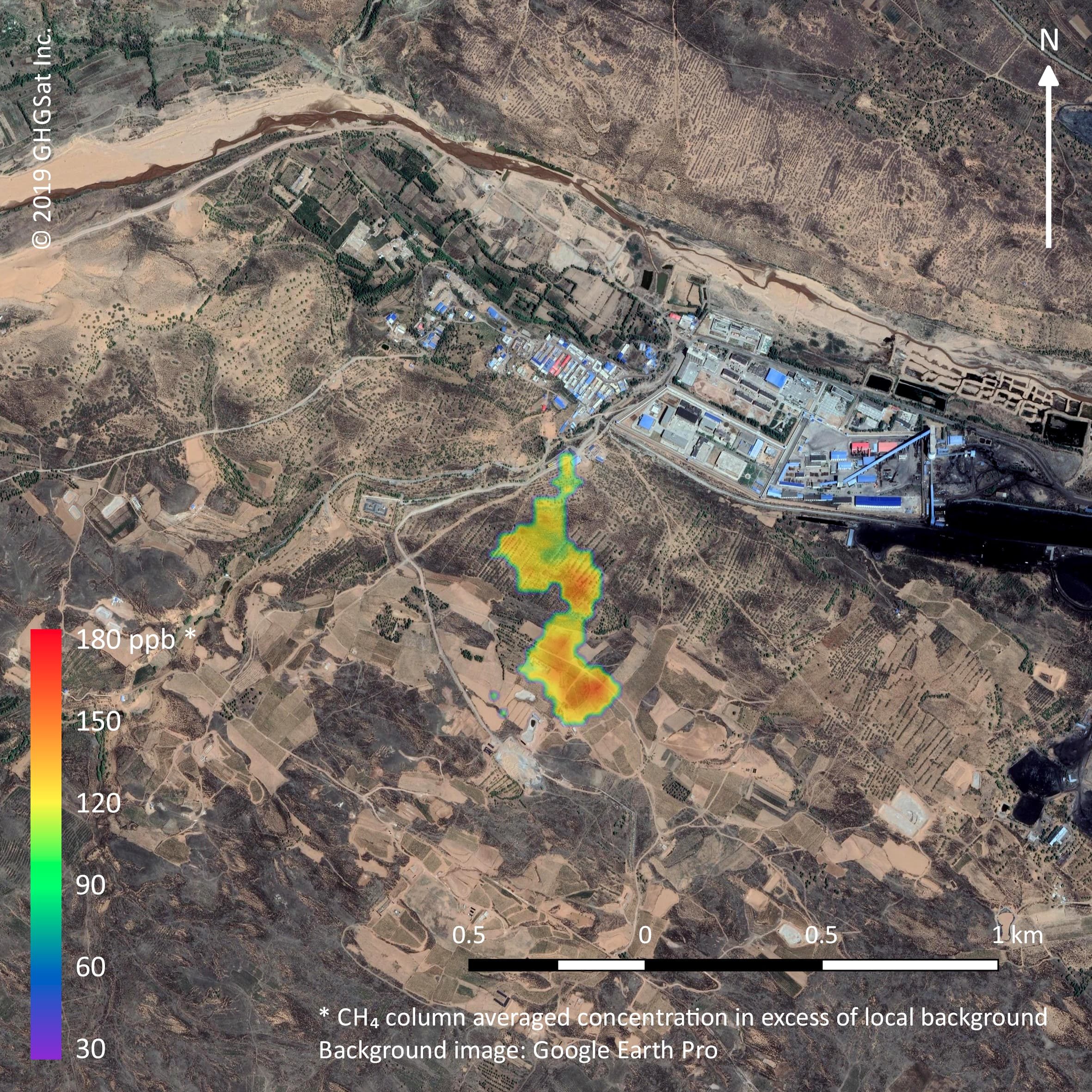

Four years into her mission, Claire continues to provide crucial data, and was responsible last year for pinpointing a massive methane leak at the Korpezhe oil and gas field in Western Turkmenistan, billowing out the annual equivalent of about one million cars on the road.

“Claire has definitely met her design life (3-5 years) and she’s still going strong,” Germain says, noting that the data gathered by the satellite has shown some important trends that could help reduce the impact of humans on the environment

“By far the most surprising thing for us is the largest emissions we see are not in Canada or the U.S., but in Central Asia. The amount of methane that we’re seeing generated in Central Asia is just jaw dropping.”

Private sector clients keen to gain valuable environmental insight into their operations sign on with the company to do flyovers of specific sites, with applications not only for the oil and gas industry but mining, agriculture, waste management and power generation as well. Germain says each orbiting platform has well over 10,000 customers per year.

So precise are the monitoring tools on Iris (as well as her soon-to-be-launched twin Hugo) that she can image and identify methane emissions from point sources as small as individual oil and gas wells, a level of data not available on any other platform.

Later this fall, GHGSat is hoping to expand global knowledge of the impacts of methane by joining forces with the European Space Agency’s Copernicus Sentinel satellites, as well as other orbiters that have similar monitoring technology, to produce the first-ever global methane emissions map.

“The map will provide a daily view of the entire planet with a higher resolution than ever before,” Germain says of the project, which initially had been slated to be revealed at the COP26 United Nations Climate Change Conference in Glasgow, Scotland before it was scuttled by the COVID-19 pandemic.

“You won’t be able to pick out individual facilities but what it will tell you is where there is more methane being produced than not.”

By providing an emissions map that will allow users to zoom into a grid as small as 2 km x 2 km anywhere on the Earth will not only help create an awareness about global hotspots of methane, Germain says, but potentially prompt action to reduces those emissions as well.

With Hugo set to join Iris and Claire by year’s end, Germain says there are no plans for the Canadian company to slow down, with eight more high-resolution spacecraft slated to join the celestial trio by 2022.

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS

Canada’s Advantage as the World’s Demand for Plastic Continues to Grow